Neutrino Beams

How to Make a Neutrino Beam

Though we’ve been making neutrino beams for decades, they’re fundamentally difficult to control and monitor. Yet understanding them is critical to our experiments.

The trouble is primarily that neutrinos have no electrical charge, so they’re hard to manipulate, shape into beams, and monitor.

The strategy to create a neutrino beam is to use a proton beam to create pions which naturally decay into neutrinos: \pi \rightarrow \mu \rightarrow \nu_\mu.

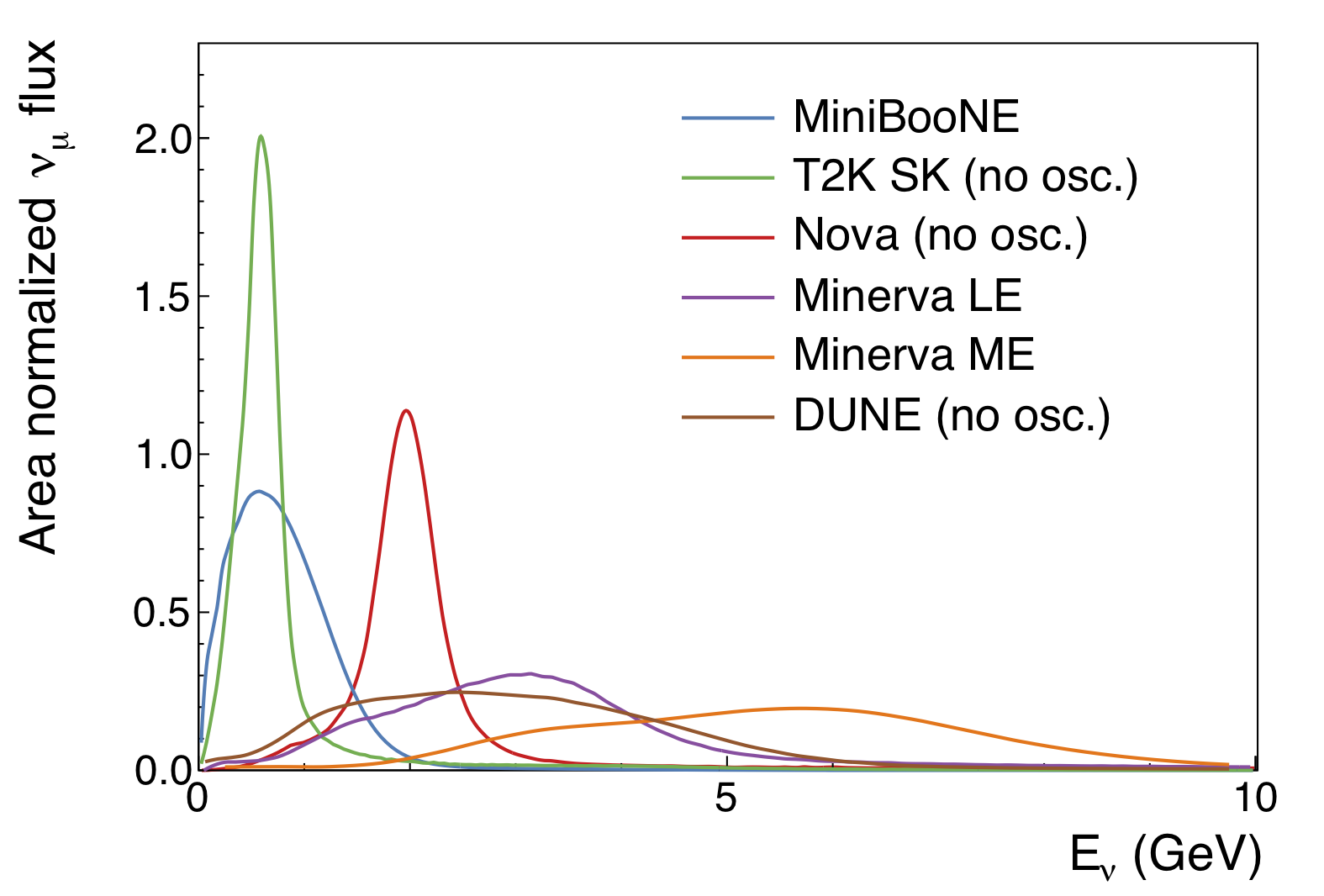

Protons and pions are charged, so by steering those with magnets first, we have some control over neutrino direction and energy. Ideally, we’d have monoenergetic and highly collimated neutrino beams, but in practice that’s not possible, and our beams are wideband.

Beam Simulation

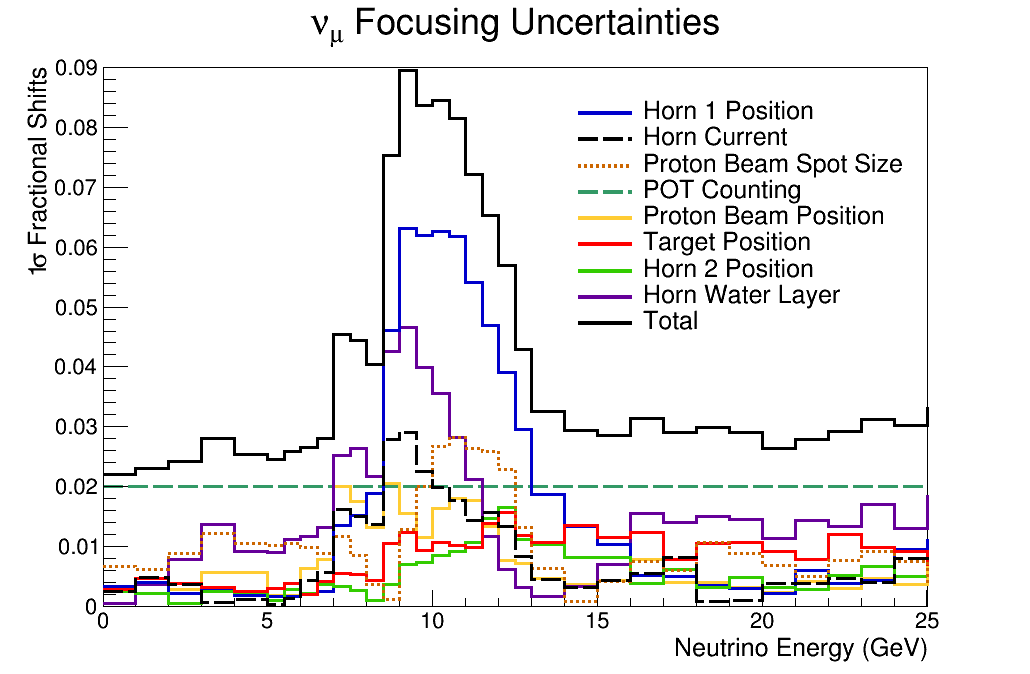

To help understand our beam and quantify our uncertaintes, we use detailed models of the entire beamline and the relevant physics processes.

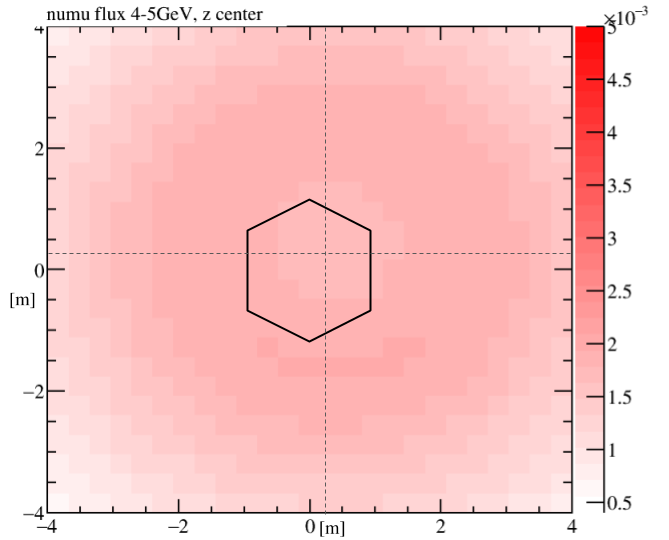

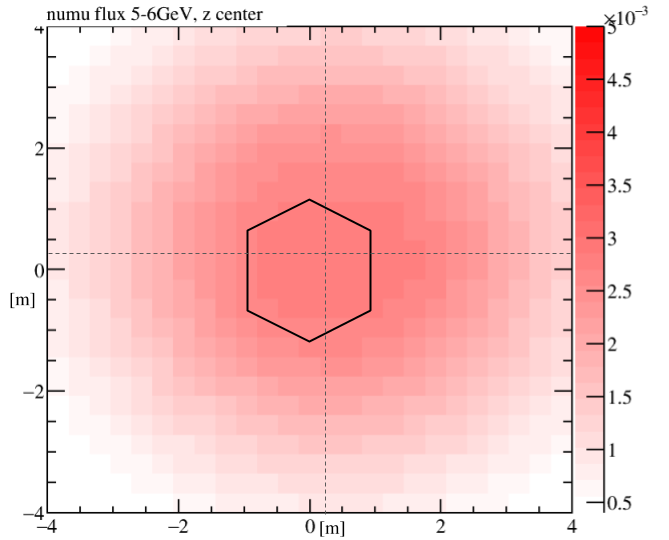

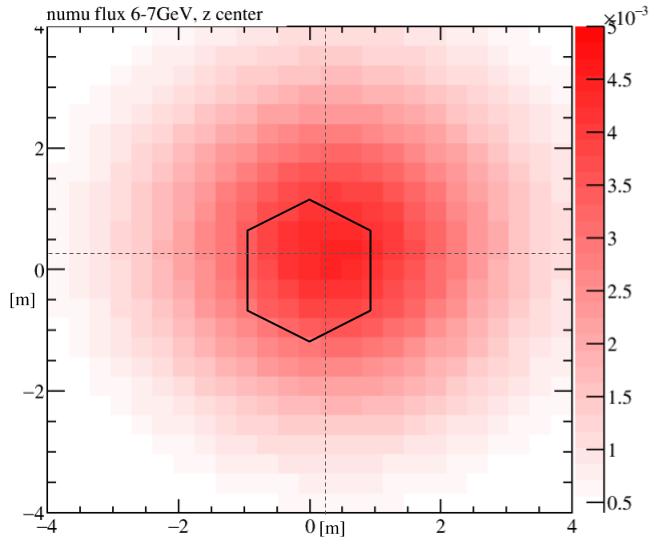

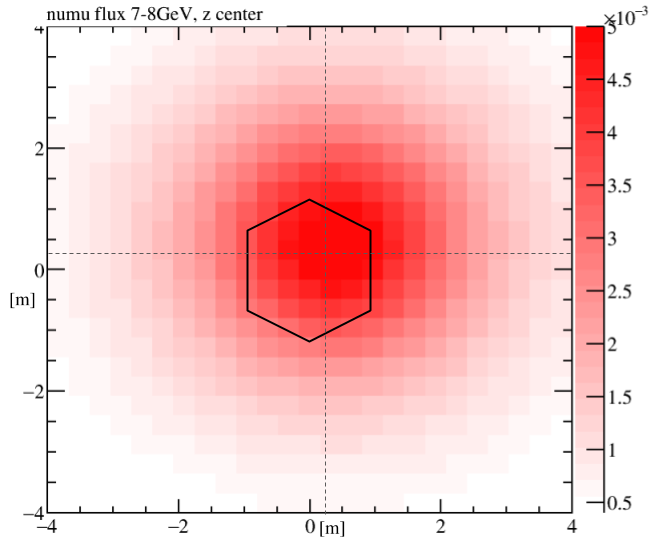

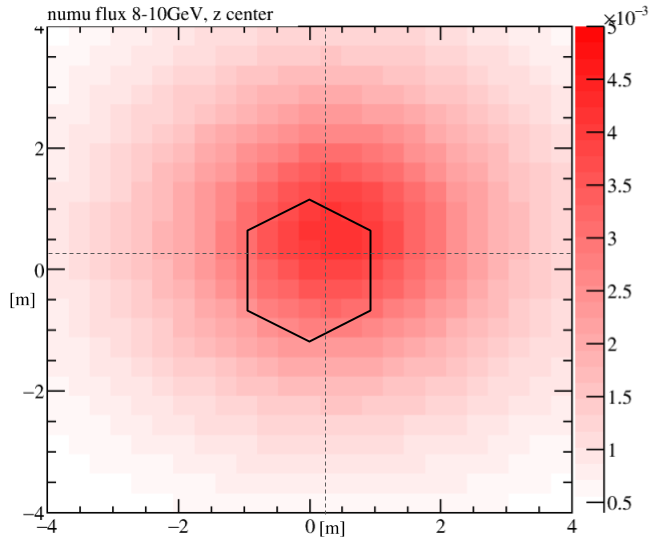

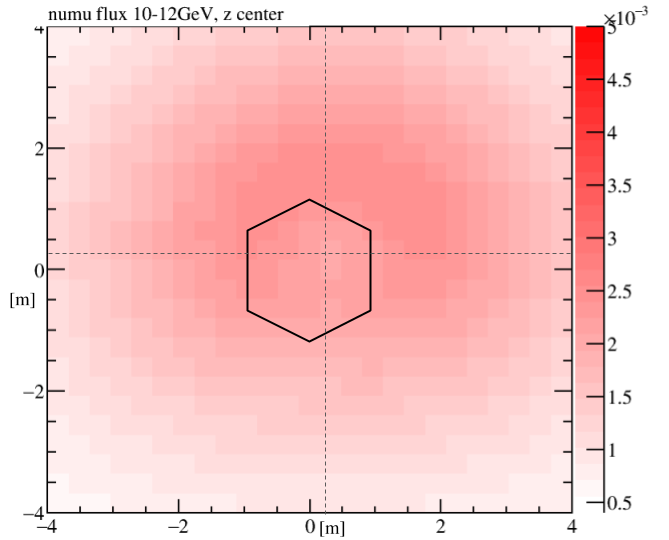

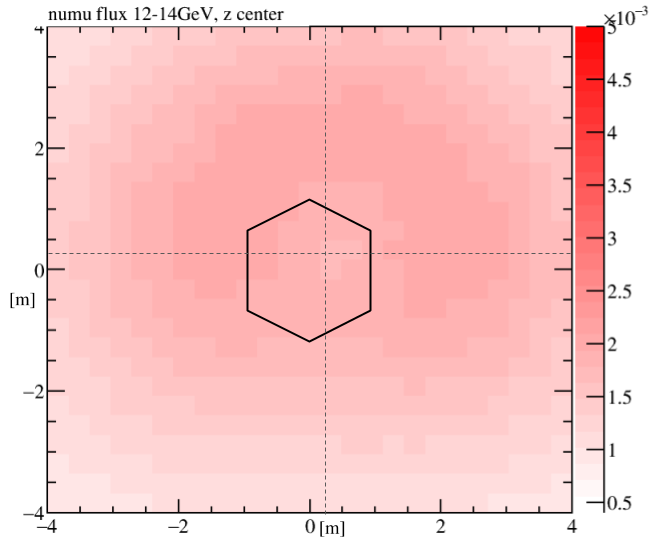

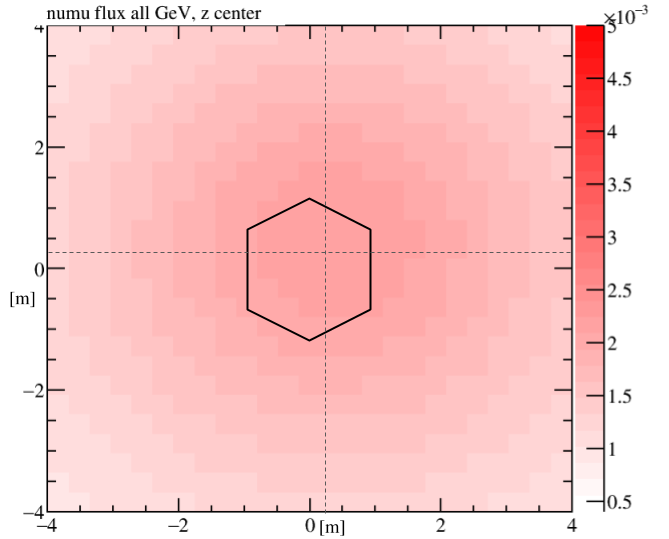

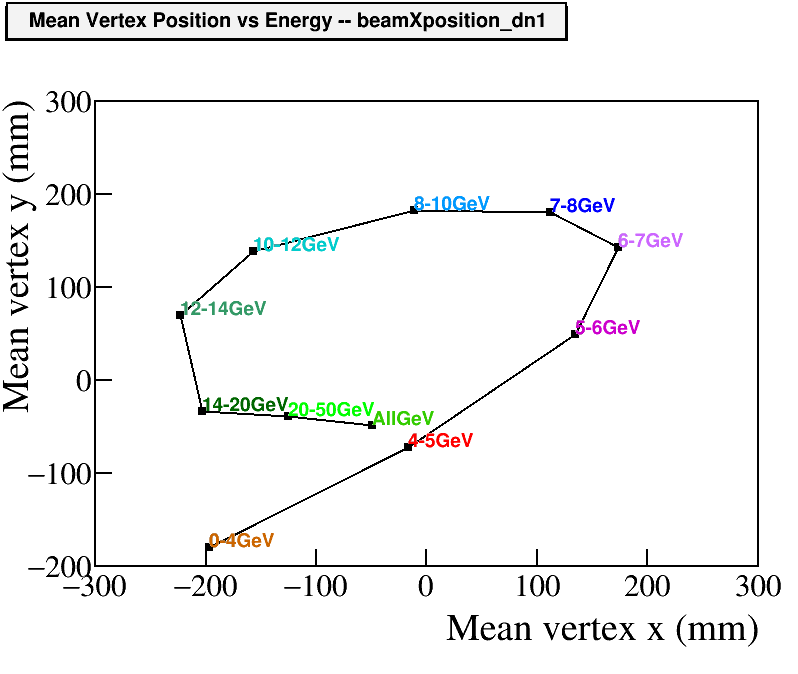

I’ve worked on many aspects of beam simulation and monitoring, but here I highlight how small asymmetries in the beamline apparatus can lead to complicated fluxes at your detector.